What the US can learn from Europe’s ESG mistakes

This article was written by Tasneem Brogger. It appeared first on the Bloomberg Terminal.

ESG investing, you may have noticed, has become a political lightning rod in the US. To liberals, it’s slowing global warming and fighting social injustice. To conservatives, it’s spoiling the economy and the American dream. So is it saving the world or destroying it? Truth is, it’s doing neither. But left to its own devices, the lucrative ESG fund industry is doing a pretty good job at destroying itself.

Bloomberg Intelligence has estimated that global ESG investment could hit $50 trillion in 2025, triple the amount in 2014. But without a common definition of what makes for good environmental, social and governance investments, fund companies have been free to slap the ESG brand on just about anything. Trusting investors often put money toward companies they might otherwise wish to avoid. Even ESG adherents sometimes have a hard time defending the label, in part because of disagreement over what it’s supposed to measure.

Companies that score ESG investments seem equally confused. By the end of April, 31,000 funds were set to have their ESG ratings downgraded by a unit of MSCI Inc., which created its first ESG-like index in 1990 and is today one of the largest firms scoring funds and companies on ESG. (Bloomberg LP, the parent of Bloomberg Businessweek, also provides ESG scores.) The changes mean that only 0.2% of MSCI-graded funds will have the highest rating in the future, compared with about 20% now, raising questions about the value of such scores. MSCI says the downgrades were spurred by client unease over the perceived “upward drift” in scores and are unrelated to regulations in Europe or elsewhere.

An even more fundamental problem for ESG investors is that MSCI ranks companies on their ability to manage risks from ESG factors, while other gatekeepers such as S&P Global Inc. consider the effect companies have on the ecosystem in which they operate. The result can be radically different grades for a single company. MSCI says it also offers tools for those seeking to invest in companies or funds that match their values.

Amid all this confusion, it’s worth looking at European regulators’ and lawmakers’ efforts to help investors allocate their capital in ways that ESG was intended. It’s not a pretty picture. Even though ESG in Europe doesn’t create the political clashes it does in the US, Europe’s ESG fund market has been roiled by continual revisions to incomplete rules, leaving clients wondering how sustainably their savings are being allocated.

In 2021 the European Union started enforcing the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation, or SFDR, to help investors figure out how much ESG bang they were getting for their buck by sorting funds into three classes. Article 9 is the highest, for funds that make ESG their “objective.” In practice, that means holding only sustainable investments, with some allowance for hedging and liquidity. Article 8 requires that funds “promote” ESG, a far vaguer mandate. And Article 6 is for everything else, but it still requires that fund managers consider whether ESG risks are relevant.

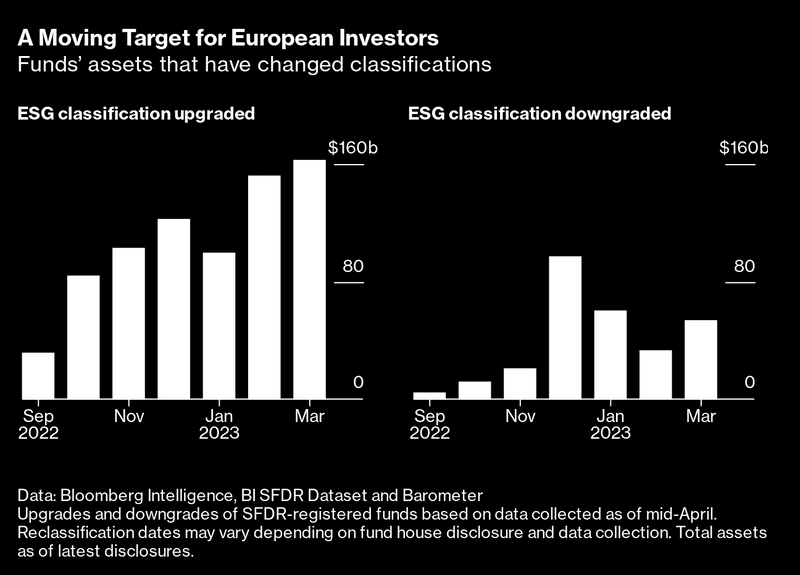

The rules resulted in asset management companies reclassifying hundreds of funds late last year to meet a Jan. 1 deadline requiring them to prove any ESG claims. Market researcher Morningstar Inc. estimates that the Article 9 designation was stripped from about €175 billion ($190 billion) worth of funds in the final months of 2022.

The turmoil continues. In mid-April, European authorities published a series of clarifications and proposals that have much of the region’s investment management industry heading back to the drawing board. Some asset managers even question whether they were wrong to downgrade their Article 9 funds in the first place.

Crucially, the EU failed from the get-go to provide a clear definition of a sustainable investment, which allowed fund managers to come up with wildly different definitions when designing portfolios. The European Commission, the EU’s executive arm and a principal architect of SFDR, has now attempted to clarify how it wants investors to treat the concept of “sustainable investment.” The upshot appears to be that asset managers will have considerable leeway, and the onus will be on investors to figure out what they’re getting with this guideline: If a company gets only a portion of its revenue from a sustainable activity, but otherwise doesn’t do any significant environmental or social harm, investors can consider that an overall sustainable investment.

“I think someone on the Commission side has gotten worried that the whole edifice of SFDR might not get the respect that it deserves,” says Eric Pedersen, head of responsible investments at Nordea Asset Management. “And so they’re trying to fix some of those things.”

The list of things to fix remains long. Article 9 is supposed to be reserved for funds that put all their money into sustainable investments, yet Morningstar said in late January that only about 6% of them are anywhere close to meeting that standard.

A November study by Clarity AI, a sustainability technology platform, found that almost 1 in 5 Article 9 funds have more than 10% of their investments in companies that violate the United Nations Global Compact principles or the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development’s guidelines on the environment and human rights. Another problem is that numerous funds were downgraded to Article 8’s vague “must promote ESG” classification. Regulators are trying to figure out how to come up with a more meaningful framework.

Late last year, the European Securities and Markets Authority, the region’s top markets regulator, added to the chaos. It said the EU should apply minimum thresholds to any funds that market themselves as ESG or sustainable. At least 80% of a fund sold under an ESG label must be verifiably ESG. If it also calls itself sustainable, at least half of the 80% must be verifiably sustainable. The idea has elicited almost universal condemnation from market participants.

The regulator is plowing through the feedback but has said it still aims to move ahead with some version of its proposal this year. If the plan ends up being enforced in its current form, Morningstar figures that only 27% of the more than €4 trillion in fund assets it estimates are registered as Article 8 could be marketed as sustainable.

None of this means ESG is doomed to fail. Pedersen at Nordea says it’s wrong to expect anything other than a drawn-out process when reimagining the laws of capital allocation. Attention to detail—in other words, data and transparency—will ultimately make the difference in whether investors understand what an ESG label really means. The US should take note.