This analysis is from BloombergNEF. It appeared first on the Bloomberg Terminal.

A new form of recycling may well shift the balance of the global waste-management game. A burst of announcements to build new chemical recycling plants in the US is pushing up domestic demand for mixed plastic waste – and even leading US to become a net importer of plastic waste for the first time.

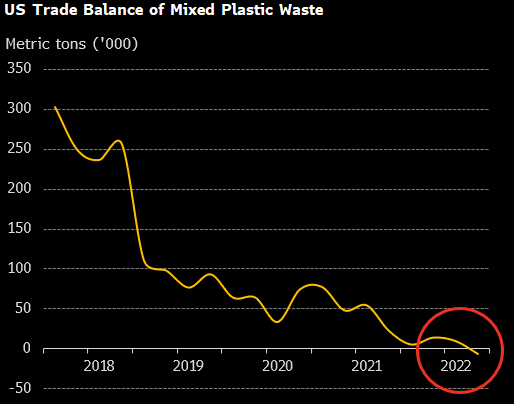

In the second quarter of 2022, the US imported 132,000 metric tons of mixed plastic waste, resulting in a net trade balance of around -6,500 tons, according to International Trade Centre data.

Chemical recycling promises better packaging plastics

Chemical recycling is set to play a crucial role in solving the plastic-waste problem. By deconstructing and reforming plastic polymers through chemical processes, it is capable of producing virgin-grade plastics from highly contaminated waste. Mechanical recycling, which represents the majority of recycling done today, tends to produce lower-grade recycled output, more likely to be used in products like garden furniture than food-packaging plastics.

These new chemical recycling processes come at a time when demand for recycled materials is accelerating. Large consumer-goods companies like Procter & Gamble and L’Oreal have set ambitious targets to increase the share of recycled content in their packaging.

In response to this demand, plastics producers like Dow and TotalEnergies are making commitments to produce millions of tons of recycled plastics. They are also investing in chemical recycling.

To date, BloombergNEF has tracked over 3.5 million tons of global chemical recycling capacity, including announced and commissioned projects. TotalEnergies and New Hope Energy have announced plans to build a chemical recycling plant in Texas that will convert over 310,000 tons of mixed plastic waste per year.

Plastic waste may become a desirable commodity

Developed economies have traditionally shipped thousands of tons of waste to developing countries. This is largely because it is cheaper to export the waste than to landfill it or build the required recycling infrastructure.

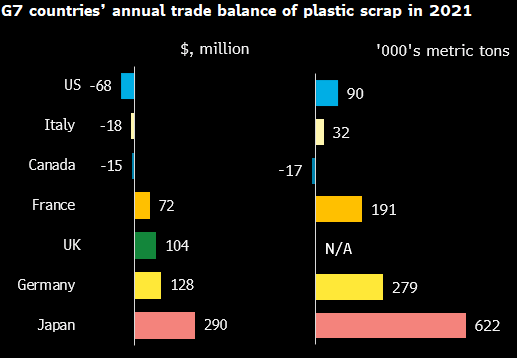

Now, however, governments are pressuring countries to deal with their waste domestically. In 2018 China, the world’s largest importer of recyclable waste, implemented the National Sword Policy, banning imports of waste from developed countries. This sparked a series of similar bans from other waste-importing countries in Asia. Nevertheless, developed countries have tended to remain net exporters of waste. In 2021 Canada was the only net importer of mixed plastic waste out of the G-7 nations, based on volume of trade.

The pressure to improve domestic recycling – buffered by the rise of chemical recycling – is changing this calculus, as the US’s recent net import of plastic waste shows. As more plastics producers invest in chemical recycling, they will need to secure supply agreements for scrap feedstock to operate their plants, pushing up demand for mixed plastic waste.

Over time, developed countries may find themselves not only needing to export less plastic waste, but actually looking to import waste to boost their own recycling markets. The result could be a reversal in the longstanding trends of the plastic-waste trade.