This article is by Silla Brush and Stefania Spezzati for Bloomberg QuickTake. It appeared first on the Bloomberg Terminal.

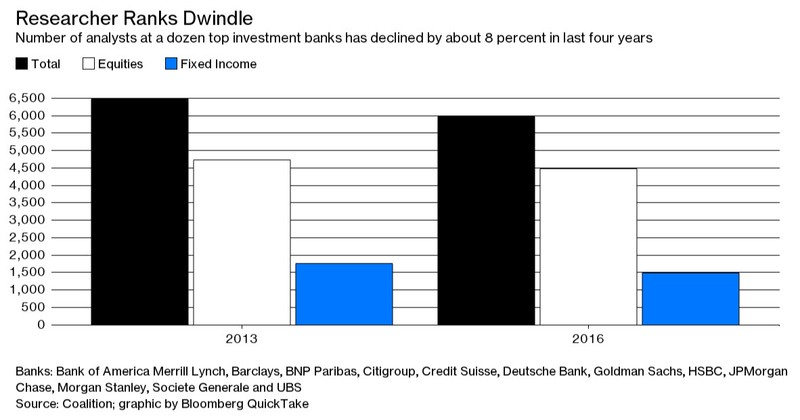

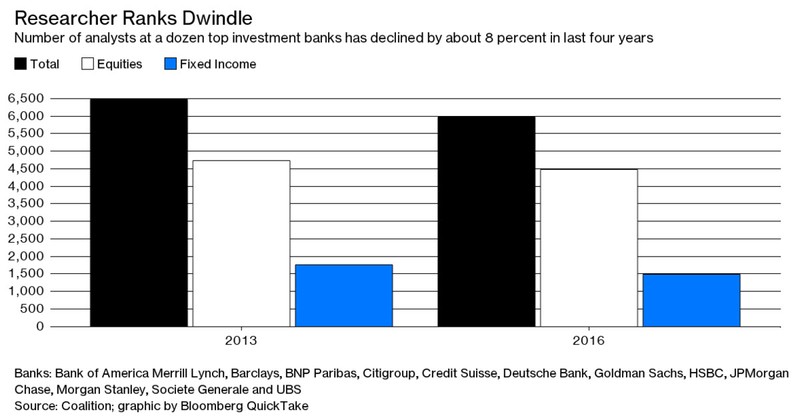

Is that research report worth more than the paper it’s printed on? That question is upending money management as new regulations in the European Union disrupt the way banks and brokers do business. Gone will be the days of offering market analysis for free, part of a bundle of services offered to clients. Soon, brokers will have to decide how much to charge for research, and for the access to top executives that typically comes with it. Some firms are modeling packages on cable TV subscriptions, running from “basic” to “pay as you go” to “all-in” offers. As the cost of an analyst’s time and work becomes transparent, investors are expected to be more selective about what they pay for. The ranks of researchers already are shrinking.

1. What was wrong with the old system?

Money managers have typically gotten research reports and corporate access — conferences, roadshows and face time with executives that can provide an information edge — as added services from the banks and brokers they choose to execute their trades. EU lawmakers wanted to root out conflicts of interest that they said left investors facing opaque and steep costs. The concern was that top money managers might route their transactions (and accompanying commissions) to the firms that offered the best tips and access, rather than the best prices for executing a client’s trades.

2. What’s changing?

European regulators’ rewrite of their financial rule book known as MiFID II comes into force in January 2018. Among its changes, it says the buffet of services attached to trading now must be bought and sold as individual pieces.

3. Is this an issue only in Europe?

No. Fund managers and brokerages run big global operations, making it likely that a European money manager will receive research from an analyst in the U.S. or elsewhere. As a result, MiFID II’s reach may be felt around the world. Already, U.S. and European authorities are wrestling with how to reconcile regulations in the two jurisdictions.

4. What has to be reconciled between Europe and the U.S.?

U.S. rules restrict brokers from receiving direct payment for research — exactly the type of requirement that MiFID II seeks to impose. However, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission is poised to grant a reprieve permitting U.S. brokerages that must comply with the European rules to sell research to clients. Meanwhile, asset managers want the SEC to clarify that they can pay for research the same way in the U.S. that they will have to in Europe. The U.K. Financial Conduct Authority is monitoring the situation in the U.S. and may respond if the conflict isn’t resolved.

4. What will the new system look like?

Active negotiations are going on between brokers and the asset managers and hedge funds who are their clients. So far it appears that:

- Danske Bank A/S won’t charge for most research.

- Goldman Sachs Group Inc. will charge $30,000 for up to 10 staff to access basic research.

- Deutsche Bank AG cut its MiFID fixed-income research price in half.

- Bank of America Corp. is quoting up to $80,000 per user for premium research.

- UBS Group AG proposes charging about $40,000 for basic research.

- JPMorgan Chase & Co. proposes charging $10,000 for equity research.

- Barclays Plc may charge $455,000 for its “gold” equity research.

- Credit Agricole SA’s priciest analyst package will start at $137,000.

- Nomura Holdings Inc. quoted $134,000 for premium research.

In the U.K., regulators said they will allow trial periods during which fund managers can receive research for free for up to three months.

5. Are fund managers going to pay?

Yes. The question is how much. Across the industry, asset managers are taking a hard look at the quality of stock and bond research they receive to determine what is worth paying for. Firms such as Woodford Investment Management, M&G Investments and Jupiter Fund Management Plc are among those that plan to pay for research out of their own profits, while other fund managers intend to continue to pass costs on to their investors in a more transparent way than in the past.

6. Will this make research better?

The jury is out. A widely held critique is that the investment industry suffers from a glut of research reports, many of questionable value. Now, analysts are rushing to prove their worth before the new rules take hold. Quality may improve as a result of increased competition from boutique and independent research firms. But there might be less coverage of small and mid-size corporations. Under the terms of MiFID II, managers that pass on costs to clients must regularly assess the quality of research they purchase.

7. Will trading fees go down?

Maybe. MiFID II requires investment firms to demonstrate that they’re getting the best execution for their clients when they trade. That additional obligation could lead to more transparency and competition, which could drive down trading fees. However, parts of the financial industry, notably the fixed-income market, have argued that research fees are already built into the price at which brokers buy and sell securities — the so-called bid-ask spread. They say the spread is unlikely to change as a result of the new regulations.

8. Will trading fees go down?

Maybe. MiFID II requires investment firms to demonstrate that they’re getting the best execution for their clients when they trade. That additional obligation could lead to more transparency and competition, which could drive down trading fees. However, parts of the financial industry, notably the fixed-income market, have argued that research fees are already built into the price at which brokers buy and sell securities — the so-called bid-ask spread. They say the spread is unlikely to change as a result of the new regulations.

9. How will it shake out?

A report by McKinsey & Co. found that banks might reduce spending on research by about $1.2 billion, a 30 percent cut. Greenwich Associates surveyed fund managers and traders and concluded that asset managers in Europe and the U.S. would cut more than $300 million from external research budgets. The number of analysts working at 12 top investment banks is down 10 percent from the end of 2012, when a headcount showed 6,634, according to Coalition Development Ltd., a London-based analytics company. Headcount may fall even lower.