FAA spending $36 billion to upgrade air traffic control system

This article is by Paul Murphy for Bloomberg Government. It appeared first on the Bloomberg Terminal.

The Federal Aviation Administration is in the midst of a planned $36 billion modernization of the nation’s air-traffic control system. Begun in 2003, the Next Generation Air Transportation System, or NextGen, has received about $7.4 billion in funding from Congress so far.

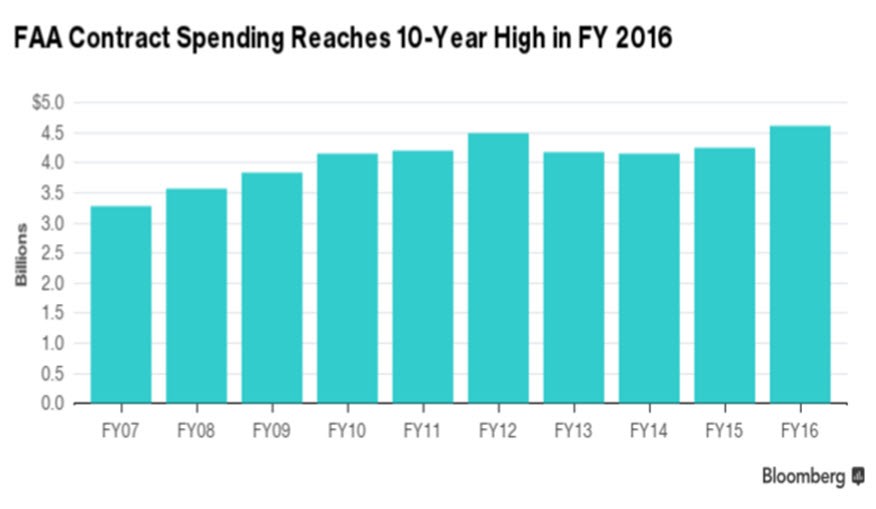

These monies, along with ongoing support for airport operations and other safety programs, translate to $4 billion to $5 billion in annual FAA contract obligations, according to Bloomberg Government’s contract database.

President Donald Trump has called the U.S. air-traffic system “obsolete” and suggested that he supports privatizing some functions of the FAA. This may represent multibillion-dollar opportunities for government contractors in the years ahead.

Trump met on Feb. 9 with airline executives and other aviation industry officials and echoed what lawmakers and executives who favor placing the air-traffic control system in the hands of a not-for-profit corporation have said.

NextGen is an amalgam of multiple new technologies designed to improve aircraft tracking, distribute data more quickly and eventually allow planes to come closer together so that traffic flows improve. The basis for many of the improvements is replacing radar, which is relatively imprecise, with GPS-generated position reports for aircraft. All but the smallest planes will have to transmit their positions with GPS by 2020.

NextGen has been a subject of concern, particularly since 2009 when, as reported by the Department of Transportation Inspector General, the program’s Joint Planning and Development Office raised the projected cost to a potential $100 billion.

The business case has scaled the program’s cost back down to $36 billion through 2030, but a DOT IG audit report renews questions about management, priorities and potential costs.

Drone risk

The increased use of private, unmanned aerial vehicles continues to add to NextGen’s system requirements, while the ever-shifting risks posed by cyberattacks raise questions about the vulnerability of IP-based communications networks used by more than one-third of FAA’s air traffic control systems.

“NextGen has been redefined, and FAA’s original vision will not be fully implemented in the foreseeable future,” the DOT IG, Calvin Scovel, stated in aletter. “Instead, the NextGen FAA is working towards today primarily emphasizes replacing and modernizing aging equipment and systems — a shift that is important but not a fundamental change in the way FAA manages air traffic.”

Rep. Bill Shuster’s 2016 bill, H.R. 4441, proposed to shift 38,000 agency employees and the air traffic control system’s assets to a user-fee-funded, federally chartered not-for-profit corporation overseen by government and industry leaders.

The Pennsylvania Republican’s proposal met resistance from House Democrats and organizations including the National Air Transportation Association and was excluded from the FAA reauthorization, though Trump’s interest may revive it.

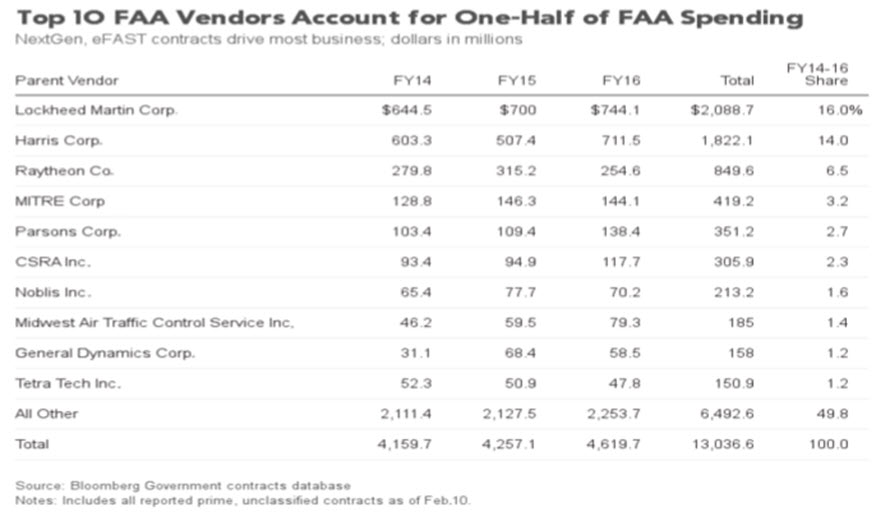

The top companies doing business at FAA in fiscal 2016 included Lockheed Martin Corp., Harris Corp., Raytheon Co., CSRA Inc., Noblis Inc., General Dynamics Corp. and Tetra Tech Inc.

FAA’s largest identified contract since fiscal 2012 has been eFAST, the preferred contract vehicle for small vendors. Other large contracts focus on different aspects of NextGen work, including Telecommunications Infrastructure, En Route Automation Modernization, Automatic Dependent Surveillance-Broadcast and National Airspace System Implementation Support.

Among the questions for vendors are how future FAA contract spending will be funded, the extent to which Congress will accommodate privatization efforts, and how Trump will react. He challenged Boeing Co. and Lockheed on large government contracts he believes cost too much, and budget hawks are looking for ways to push more spending off-budget.