Inflation Reduction Act: US elections can reshape health care sectors

Bloomberg Intelligence

This analysis is by Bloomberg Intelligence Senior Analyst Nathan Dean. It appeared first on the Bloomberg Terminal.

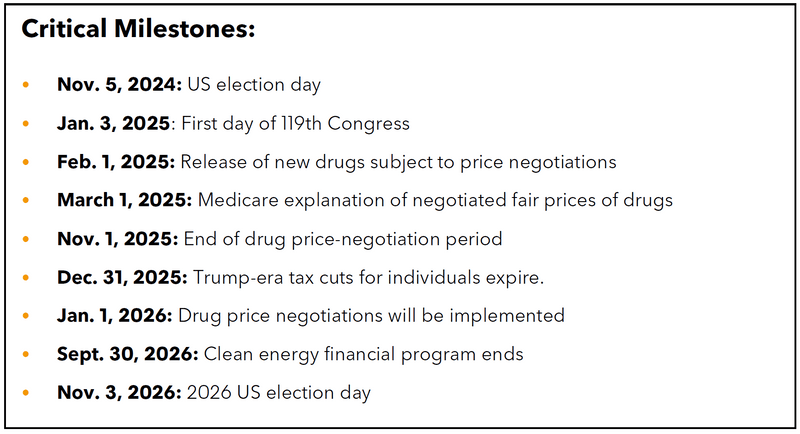

The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) of 2022 will be subject to several key catalysts over the next few years. The US election on Nov. 5 could bring in new lawmakers who may seek to defend or restrict the law, which also includes three years of Affordable Care Act subsidies. The scheduled expiration of tax cuts enacted under Trump signals further debate is likely before the end of 2025.

Master negotiator or bare minimum?

The IRA sets out minimum price cuts for negotiation-eligible drugs of 25-60% off the average manufacturer price — based on time elapsed since FDA approval — or no higher than current prices after rebates. As president, Trump could negotiate steeper price cuts or do the bare minimum. He isn’t a fan of the pharmaceutical industry. Though Trump changed his view on negotiating authority — supporting it as a candidate but opposing it as president — his administration proposed but didn’t implement a policy tying Medicare prices of some drugs to those of other countries. He also created the framework to allow drug imports from Canada, which the industry opposes.

If elected, Trump could use his regulatory authority to make Medicare rules for IRA drug negotiations more pharma-friendly. Biden’s Medicare agency issued final guidance in 2023 interpreting a “single-source drug” as one without “bona fide” generic competition and thus eligible for cuts. “Bona fide” isn’t in the IRA statute, and a determination of what’s a generic will be made on a case-by-case basis that weighs factors like generic utilization included in prescription-drug event data.

The agency also defines a single-source drug based on its active ingredient, enabling the grouping of multiple therapies with a different drug or biologics license application — like Novo’s Fiasp and NovoLog — that are eligible for cuts. These regulatory interpretations could narrow in guidance under President Trump.

The Biden administration will release the first set of price cuts to Part D drugs selected for negotiation by Sept. 1. Though Biden hasn’t benefited politically from the IRA’s drug-pricing provisions, repealing them after an expectation of lower prices might have political downsides. Gross Medicare spending exceeded $50 billion on the 10 Part D drugs subject to negotiation during a 12-month period in 2022-23.

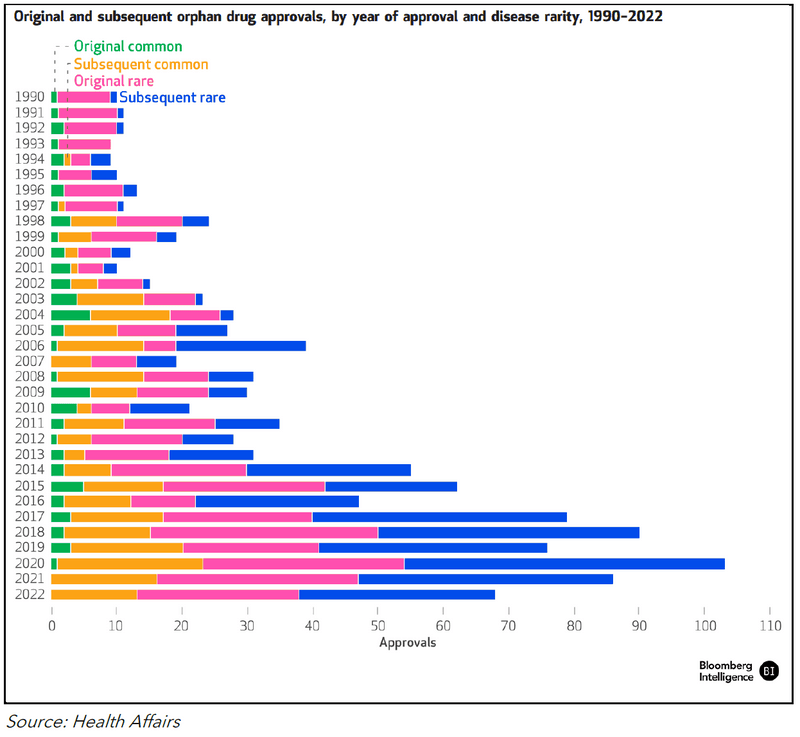

Figure 1: Drug Negotiation List (2026 and Projected 2027)

Medicare drug spending sets tone for next targets

AstraZeneca’s Symbicort and Astellas’ Xtandi are likely top targets on the next IRA drug-negotiation list, set for release on Feb. 1, 2025. Semaglutide (Novo Nordisk’s Ozempic and Rybelsus), Myrbetriq, Trelegy Ellipta and Symbicort led Medicare spending in November. Generic and biosimilar entry could influence whether a brand drug is included on the negotiation list or removed before government price cuts are implemented.

Under the IRA, drugs must be FDA-approved for seven years — 11 for biologics — by the selected drug-publication date to be eligible for negotiation. Medicare spending from June 2022-May 2023 determined the list of 10 Part D drugs selected for negotiation ahead of the price cuts beginning in 2026.

Ozempic, Ibrance and Trelegy Ellipta were approved in 2017, making them eligible in 2025, with prices effective in January 2027. Medicare drug-expenditure data for a 12-month period that ends no later than Oct. 31, 2024, will guide selection of those eligible for the 2025 negotiating round in that sets prices for 2027. There will be 15 Part D drugs eligible in 2027, 15 Part D and B drugs in 2028 and 20 each year after.

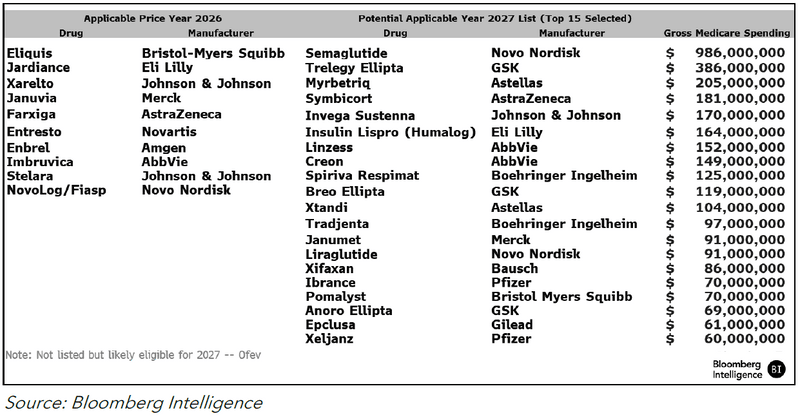

Some of the drugs on our list might avoid negotiated pricing in 2027 due to generic or biosimilar competition, which tends to drive down prices, as seen in Figure 2. Generic competition in 2024 is possible for Novo’s Victoza, while a Humalog interchangeable is possible by 2026.

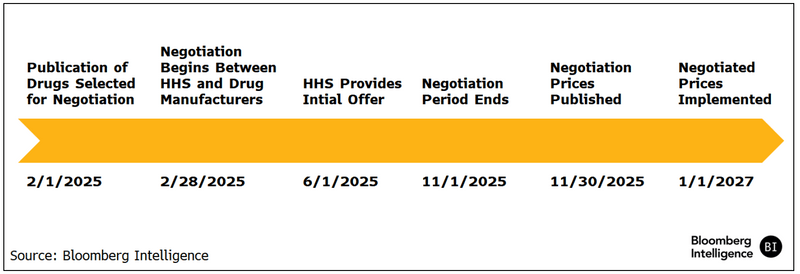

The timing of generic entry will be key. If Medicare determines that a generic is authorized and sufficiently marketed before the end of the price-negotiation period — Nov. 1, 2025 — the negotiated price won’t apply. If marketed after the negotiation period but before March 31, 2027, the negotiated price would stick through 2027. If marketed April 1, 2027, or later, the negotiated price extends through 2028.

The negotiated price is 25-60% off the non-federal average manufacturer price (non-FAMP). That’s typically 80% of the list price, based on government data.

Medicare’s threshold for determining whether a generic is marketed enough to spare its reference drug from price cuts might be low, based on the negotiation list for the first 10 Part D drugs released in August, but its application in future rounds bears watching. The agency can keep a drug off the list if there’s “bona fide” marketing of its generic or biosimilar, which is tied to utilization and other circumstances. Medicare guidance doesn’t provide a minimum threshold of what constitutes “bona fide,” but biosimilar competition to AbbVie’s Humira might offer clues.

Humira would have qualified for negotiation, based on gross Medicare spending, but likely didn’t with eight biosimilars licensed — even though it had 99% of market share through May. This may suggest a broad interpretation of “bona fide” marketing.

Figure 2: Price Analysis of Generic Entry (2015-2017)

Figure 3: 2027 Applicable Price Year Negotiation Timeline

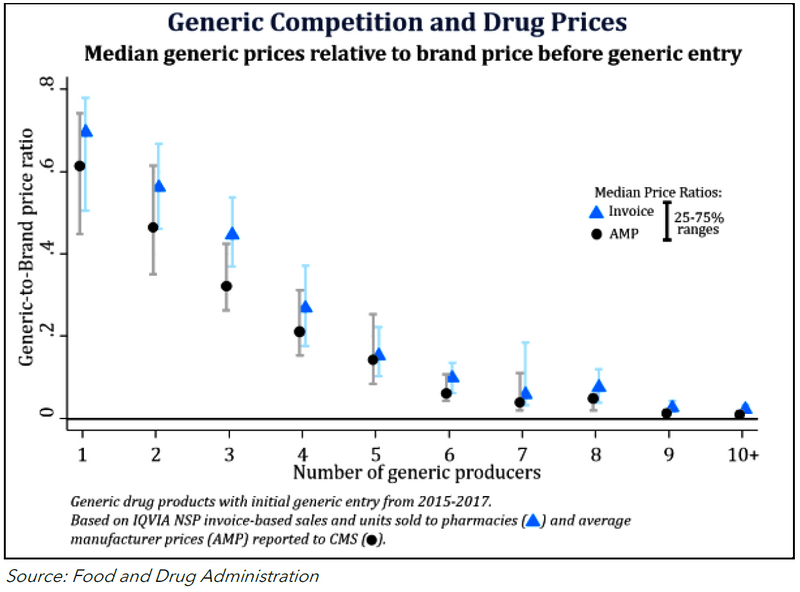

Orphan drug care-out is unfinished business

Alnylam, AstraZeneca, Relay Therapeutics and other drugmakers would be helped by a bipartisan proposal to exempt orphan drugs that treat more than one rare disease from price cuts, but it might get a better reception from Congress after November’s elections. The effort builds on the new legislation to exempt small-molecule drugs from negotiation for 11 years after FDA approval.

Hearings by the House Energy and Commerce Committee created headline noise about orphan-drug exemptions in the IRA but didn’t shed light on a pathway for modifications. The IRA exempts from negotiation orphan drugs designated for only one rare disease or condition where the approved indication is only for that illness or condition. Drugs with designations for multiple rare diseases or conditions aren’t exempt.

The ORPHAN Cures Act would exclude from negotiation orphan drugs designated for one or more rare diseases or conditions. But some committee Democrats say expanding the exclusion could undermine the IRA by removing high-spending drugs from negotiation.

There’s concern from both parties about disincentives to conduct research for rare diseases that affect fewer than 200,000 people in the US. Though few true orphan drugs might meet the $200 million expenditure threshold that triggers negotiation, additional indications for other orphan or common diseases are possible and could result in added spending that exceeds the bar.

That could prompt companies researching rare diseases, like Alnylam and AstraZeneca, to re-evaluate their pipelines in light of the government’s ability to cut drug prices years before the drugmakers recoup their investments. The IRA might make drugmakers more likely to delay new indications for small populations and pursue larger populations first to maximize opportunities to recover investments before prices are reduced.

Figure 4: Orphan Drug Approvals (1990-2022)