Treasury rules, not new tax laws, are poised to have most bite

This analysis is by Bloomberg Intelligence Government Analyst Andrew Silverman.

The stock-redemption tax is too small to change large corporations’ behavior. Rules giving the IRS the ability to recast derivative payments as dividends, however, could shift the nature of shareholder returns. Though the IRS initially stumbled on taxing cryptocurrency staking rewards like dividends, we think that’s only the initial battle in a much longer war.

Redemption levy akin to a fine, not a tax

The buyback tax was probably adopted because it’s not potent and so won’t change companies’ behavior. The 1% levy is expected to cost companies about $6 billion annually, according to the Tax Foundation, vs. a 1 percentage-point corporate-tax boost estimated to cost about $100 billion a year. The tax only took effect on Jan. 1, but it doesn’t seem to have slowed repurchases. Among S&P 500 members, buybacks have totaled $1.97 trillion in the past 12 months, including Wells Fargo’s $30 billion deal announced July 25. That’s fallen from $2.12 trillion year-over-year, but buybacks during the last two years have far exceeded previous years.

Apple paid $19.6 billion in income tax last year and Amazon $6 billion. In context, the buyback measure is little more than a fine, so may not significantly affect shareholder distributions

Crypto staking rewards might become dividends

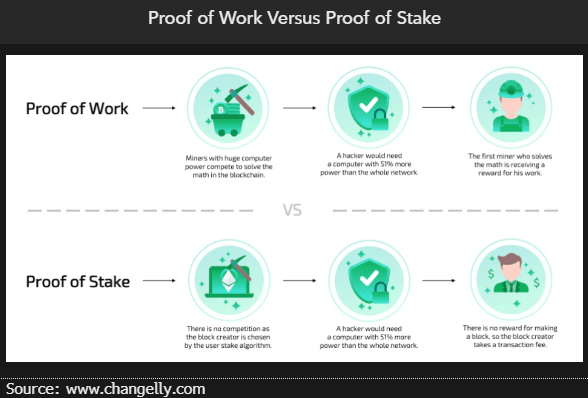

The IRS offered a refund in a recent case where the agency had claimed that a staking reward was taxable upon receipt, akin to a dividend, but we think that’s atypical. A taxpayer sued the IRS in 2021 for taxing his staking reward, a payment in kind for validating a block of transactions on a blockchain. Without officially accepting the taxpayer’s argument, the IRS issued a refund and the case was dismissed, preventing precedent being established. The agency’s options, therefore, are still open. Since then, the New York State Bar Association has submitted a report to the Treasury Department supporting the government’s view.

The Lummis-Gillibrand Responsible Financial Innovation Act, the only comprehensive crypto legislation proposed by Congress, would, however, postpone taxation until the staking reward is sold.

Equity-derivatives taxes might increase

Though distributions on many derivatives are temporarily exempt from tax, the waiver is set to expire in 2025. For those distributions potentially subject to tax, the decision on whether they’ll be taxed, and when, is Treasury’s alone. Structured products such as basket swaps are most affected. Distributions on equity derivatives are only taxed like dividends if the derivative closely resembles a US stock, such as a total-return swap. Until 2025, only derivatives that have at least an 80% overlap with one or more US stocks are subject to dividend withholding tax.

Congress estimated in 2008 that shareholders could pay as much as $100 billion in withholding tax on dividend-equivalent payments annually. That’s probably an over-estimate. In 2020, the latest year for which we have data, about $1.23 billion was paid.

Regulatory tax changes in focus in 2023-24

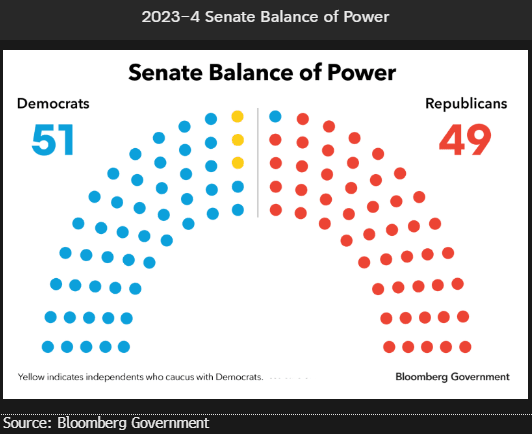

With Republicans in control of the House and Democrats the Senate, it’s likely that the biggest business-tax changes through 2024 will come from Treasury regulations. At best, Congress will only be able to enact limited tax changes, so much of the action will shift to tax guidance from the IRS and Treasury Department. Treasury is mainly focused on instructing taxpayers about how to apply the Inflation Reduction Act tax statutes. The Treasury also has a broad mandate to create new rules, especially in the areas of M&A, financial products and transfer pricing.

Congressional inaction invites a more aggressive Treasury Department, and we think the Inflation Reduction Act gives the IRS a mandate to step up enforcement.

Supreme court hail-mary could provoke chaos

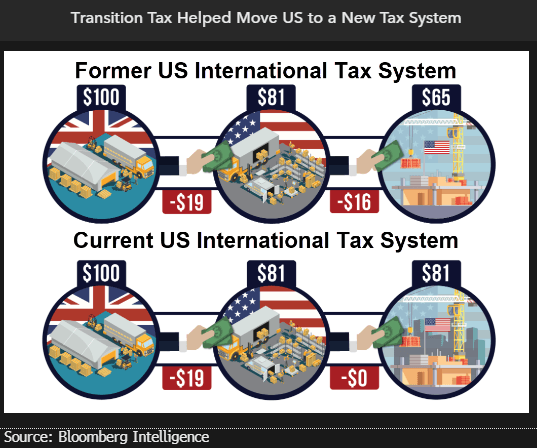

A pending US Supreme Court case remains the biggest uncertainty on US dividend taxation as it could upend 50 years of cross-border dividend-tax law. The case addresses the legality of the 2018 transition tax that deemed all untaxed offshore business income held by US companies to be repatriated and taxed in the US. The principle at issue, the ability of the IRS to tax income that hasn’t been repatriated, is an essential element in US international tax. Even if the court strictly limits its ruling and strikes down the transition tax, it would still open many other international tax rules to judicial challenge.

We don’t think the Supreme Court would invalidate the transition tax — lower courts have all upheld it — but the fact that the high court chose to hear the case at all has raised concerns.