ARTICLE

Does climate leadership drive financial performance, or is it the reverse?

Bloomberg Professional Services

This article was written by Niall Smith, Senior Sustainable Investments Quantitative Researcher at Bloomberg.

In this article we test the hypothesis that more profitable companies are more likely to set climate targets. Our analysis reveals that, in a broad cross-section, more profitable firms (top decile) have 3.5x higher odds of having a net zero target than less profitable firms (bottom decile), holding sector constant. This pattern suggests that companies may set targets, not solely because they believe that decarbonizing will improve their financial position going forward, but because their already strong profit margins provide the financial headroom to make such commitments. It highlights that the presence of a target alone is an incomplete signal of a firm’s intention to transition to low carbon, and the importance of considering broader indicators of transition credibility to provide a more complete picture. Finally, we note that screening portfolios on net zero target status may inadvertently tilt towards profitability/quality and away from other styles, a potential bias worth noting.

Driving forces behind the wave of corporate climate targets

We posit that there are two general sources of motivation for why companies choose to set climate targets. First, companies might determine that in an increasingly carbon-constrained environment, establishing targets will ensure they have clear goals to work towards, and make timely steps towards reducing energy consumption, improving efficiency and reducing GHG emissions. They might hold the belief that this will reduce their operating costs and drive increased profits in the long run. If these intrinsic, operational motivations dominate then we’d expect to see companies setting targets regardless of their profit margins.

On the other hand, firms might choose to set targets, not because of a belief in direct benefits to their bottom line, but because of competitive positioning. Companies might want to strategically signal to the market that climate action is a priority for them, to stay afloat with target-setting activity amongst their peers, thereby preserving their reputation with stakeholders like investors and customers. In other words, their motivations might be more extrinsic. If this is more often the case, we might expect target adoption to occur more frequently when a company’s financial conditions can accommodate it.

Decoding who sets targets and why

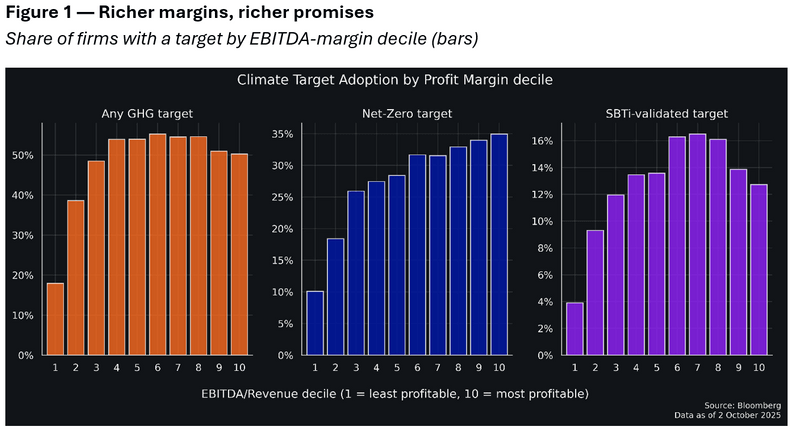

We analyzed a large universe of publicly listed companies to understand the relationships between firm-level financial performance and the presence of climate targets, considering three different target types. We used data available on the Bloomberg Terminal (ESGD CARBON TARGETS <GO>) to look at whether companies had set any GHG target at all, a net zero target and finally, an SBTi externally validated target. Profitability was measured through the latest value for EBITDA margin (EBITDA/Revenue). We first grouped the entire sample into 10 equally sized bins in terms of profit margins. Figure 1 below illustrates the proportion of each group (decile) with a climate target of each type. The overall prevalence of these target types differs as expected, with generic GHG targets being the most frequently set (48%), followed by net zero targets (28%) and finally SBTi-validated targets (13%).

However, a more notable takeaway is that a clear increasing trend is seen with net zero target-setting through the profitability bins. There is also a rise in the portion setting more generic GHG targets, and SBTi-validated targets as profitability increases, but the pattern isn’t quite as clear. In all cases there is an obvious drop-off in targets in the low-profit groups. This suggests that climate target setting falls down the list of priorities for firms that are more cost constrained and operate with thinner margins.

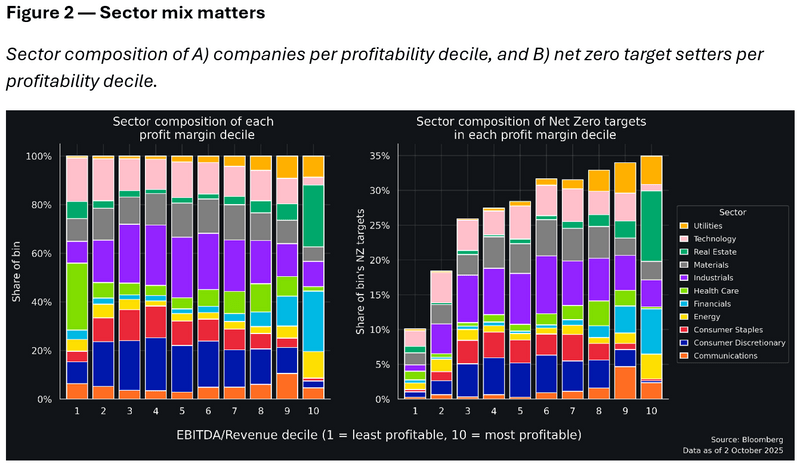

Naturally, some sectors populate the higher profit bins more often. It is well understood that due to the cyclicity of economic sectors, different business models, technology maturity and reliance on R&D, some sectors are inherently more profitable than others. At the same time, we would expect target adoption to be more frequent in some sectors than in others. To illustrate this further, Figure 2 shows the sector mix through the profit margin deciles on the left pane, reflecting the fundamental characteristics of economic sectors. The right pane shows the sector mix of net zero target setting companies in the same groups. We can see that the greater prevalence of target adoption is partially a sector story.

Utilities occupy a greater share of the most profitable group, and we might also expect them to set climate targets more frequently than firms in other sectors. The sector is very high-emitting and also has many opportunities to decarbonize through viable and scalable low carbon alternative technologies. Conversely, health care companies tend to operate on thinner margins and (arguably) we might expect firms in this sector to be less likely to set climate targets, acknowledging that they are less material from an emissions standpoint.

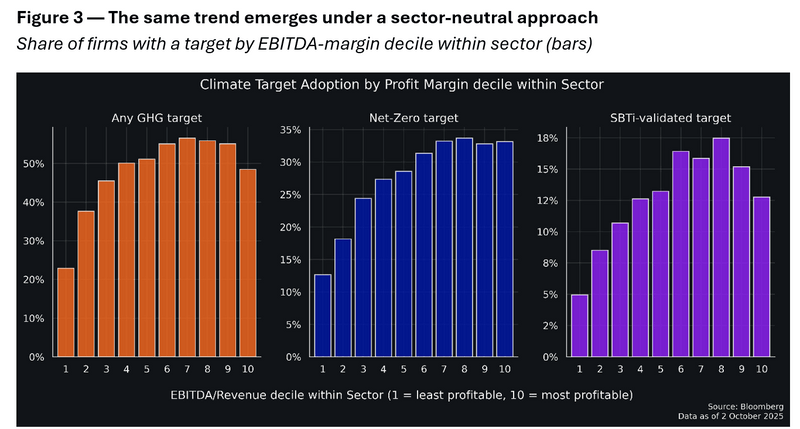

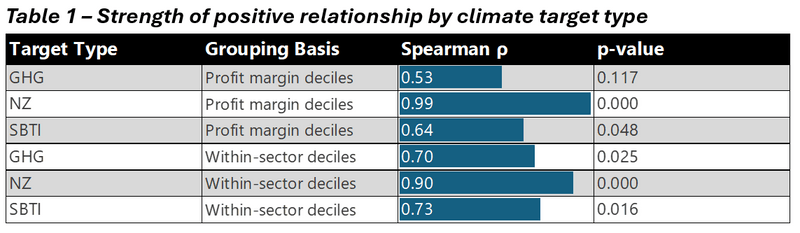

We then repeated the analysis but took a more sector-neutral approach. In this case, companies are assessed on their level of profitability relative to their sector peers. The highest decile bin is comprised by the most profitable 10% of companies in each sector, and the lowest decile bin by the least profitable 10% in each sector. This counteracts the effects of sectoral differences in profitability and concentration. Interestingly, the monotonic pattern is still mostly preserved, as demonstrated by Figure 3. Once again, it is with net zero targets that we see adoption rising most steadily in line with the level of profitability versus sector peers.

To formally test for a positive monotonic association, the rank correlation coefficient (Spearman’s ρ) was calculated in each of the cases above. When this value is closer to 1, it is evidence that the prevalence of targets increases consistently as profitability rises. When the corresponding p-values are smaller (i.e. closer to zero) it indicates that the observed trend is less likely to have occurred by chance. Table 1 below summarises these investigations and demonstrates how the trend is clearest with net zero targets. While the relationship does become slightly weaker after sector neutralisation, with the increase in targets plateauing after decile 7, it is still a noteworthy finding.

Maximizing reputational risk-to-reward

The trend is strongest with net zero targets over the other types, and we explored some reasons why this might be the case. For the more generic GHG target adoption, this might be because less profitable companies (e.g. bins 3-4) perceive it as low risk to make some kind of emissions reduction commitment, without being too precise in terms of the level of ambition, and without the oversight and scrutiny of an external validation process. Whereas for SBTi targets, the additional hurdles needed to set and validate targets, as well as a perception of short-term costs, might be enough to constrain adoption even among some of the more profitable companies.

Net zero targets might be something of a middle ground for companies: a strong signal of ambition with an apparent link to wider climate goals through an industry-recognized term, but without the scrutiny and administrative overhead incurred by an external validation process. And this is where we see target adoption rising most steadily in step with stronger profit margins. Companies may send a strong signal of ambition to the market but with a relatively moderate process cost. Note that the mechanisms described here are simply plausible explanations consistent with what we have observed from this analysis, but they do not yet establish causality.

Profit margins or sector: which matters more?

We wanted to investigate this more explicitly and tease apart how much sector membership is responsible to target adoption, versus the “profitability effect”. We fit a simple additive logistic model to predict whether a given company has set a net zero target or not, including sector-level fixed effects as well as information on profitability within sectors. The model is not designed for accurate firm-level predictions, but rather as a tool to help us understand and explain the overall patterns of target adoption.

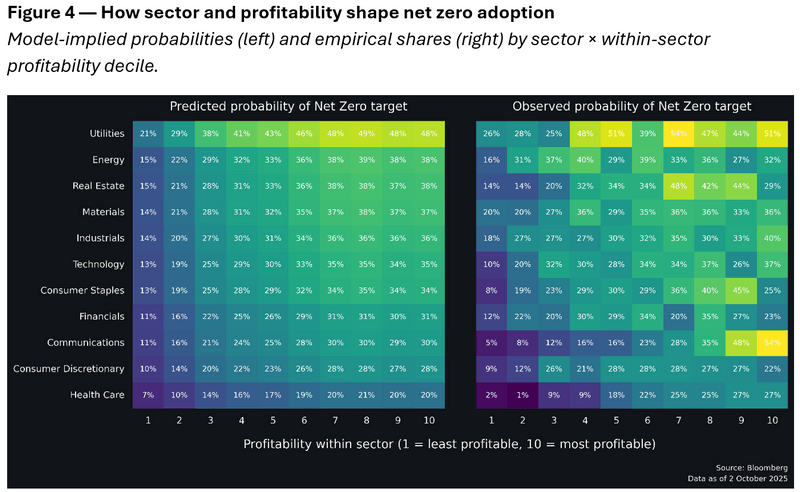

Averaging across sectors, the model estimates that firms in the top profitability decile have about 2.5× higher probability of having a net zero target than those in the bottom decile (≈33% vs 13%, +20 percentage points). It also reveals that profitability is a more dominant driver of net zero target status than sector membership, at least in this specification. When we decompose the model’s predicted probability surface, about two-thirds of the variation (≈63–65%) is tied to profitability, and about one-third (≈35%) to sector membership. Figure 4 visualizes the probability grids by sector and profit margin deciles, with the model’s predicted values on the left and the observed values on the right.

This model is coarse given its simple design, so naturally it will not match every sector and decile combination exactly. Nevertheless, it is helpful to quantify and communicate the broad patterns seen in the data and demonstrates how each of the key dimensions of profitability and sector shape the landscape of corporate net zero target-setting.

From surface-level signals to deep credibility assessments

This analysis supports the hypothesis that profitability enables climate target-setting, rather than the reverse. The results suggest that healthier profit margins provide the headroom a company needs to set climate commitments. This intuitively aligns with resource-based theories around corporate sustainability, according to which only firms with sufficient financial slack can afford to engage in voluntary sustainability initiatives. This is not to say that profitable firms cannot also be genuine climate leaders, but the strength of the pattern we’ve observed suggests that targets often function more as indicators of financial capacity than as reliable proxies for decarbonization intent.

There are limits to what this analysis can establish, given its cross-sectional nature. Future research should look to add a temporal dimension, for example through longitudinal testing and events studies that factor in the cyclicity of profit margins and the precise timing of target announcements. This would help to further determine directionality and address whether climate leadership drives financial performance, or the reverse.

For investors, this analysis builds upon an already familiar idea: that climate targets on their own are a weak and incomplete signal of climate ambition. Companies may be establishing targets only once their financial conditions allow, rather than being climate leaders regardless of whether they are facing headwinds or tailwinds. A net zero target is best substantiated when it is accompanied by a comprehensive and realistic climate transition plan, which outlines governance and oversight, incentives, decarbonisation levers and plans around transition finance. Investors taking into account disclosed climate ambition therefore may wish to further distinguish between companies setting surface-level climate commitments and those with deep decarbonisation intentions by integrating analysis using a much broader set of transition credibility indicators.

The findings also have a clear implication for portfolio construction. Investors that use climate target status for as a screen or universe filter might be embedding a profitability/quality tilt, which can diminish exposure to other styles. Investors may wish to note this potential bias and how it could affect factor exposures.

Technical notes

The starting universe for the data collected for this analysis was the BESGCOV, which includes approximately 17k companies across markets globally. After accounting for coverage across relevant data fields, the core analysis covers approximately 15.1k companies.

Determining the larger driver of net zero target adoption (within sector profitability versus sector membership) was achieved through ANOVA-style split in combination with a Shapley split of explainable deviance. Variance splits are reported on both the probability and deviance scales; results are consistent across both tests.

Data on company climate targets is available on the Bloomberg Terminal at ESGD CARBON TARGETS <GO>.

Data on company transition plan credibility is available on the Bloomberg Terminal at ESG NETZ <GO> and ESGD TRANSITION PLAN <GO>.